Theory of Light and Color

29. Light and Color Rendering: What is Color Rendering?

(1) How to See Object Color

The way we perceive the color of objects in our daily lives is determined by a combination of three elements: the spectral distribution of the light illuminating the object, the physical properties of the object itself (spectral reflectance), and human vision characteristics (refer to Chapter 12). This means that even for the same object, the physical properties of the light reaching our eyes change under different light sources, and the perceived color is determined by these factors combined with our visual perception. The influence of lighting on how the color of an object appears is referred to as "rendering," and the specific property of a light source that determines this rendering effect is called "color rendering."

Throughout human history, our ancestors lived under the light of the sun during the day and the light of bonfires or lanterns at night. It's in our DNA to naturally perceive the colors of objects under these light sources as the most natural. ≪1≫ We unconsciously remember and recognize the "appropriate" colors for various types of objects, and when we see objects illuminated by artificial light sources with characteristics (spectral distributions) different from sunlight or lantern light, they may appear unnatural or less desirable.

In the late 19th century, Joseph Swan and Thomas Edison invented and commercialized the first artificial white light sources (incandescent bulbs). In the more than 130 years since then, fluorescent lamps, mercury lamps, sodium lamps, xenon lamps, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and other artificial light sources have been developed and put to practical use. Depending on the specific lighting conditions, objects illuminated by these lights can appear in various colors even if they are the same object.

Therefore, when deciding on a light source to use, we have to evaluate the characteristics of how colors appear under that light source (the quality of its color rendering) in relation to its intended use.

(2) The Concept of Color Rendering

The way objects appear in color is primarily determined by a combination of the spectral distribution of the illuminating light and the physical properties of the object (spectral reflectance). However, actual perception is also physiologically and psychologically altered by vision properties. When considering the color rendering of lighting, we need to account for chromatic adaptation, ≪2≫ a factor directly related to the characteristics of the light source among the various factors affecting how colors appear due to visual characteristics.

Under these circumstances, the color rendering of lighting is determined by the combination of two factors:

(1) The characteristics of the light source (spectral distribution) – physical factor.

(2) The chromatic adaptation caused by the light source – physiological and psychological factors.

For factor (1), the light that enters the eye has the spectral properties of the product (P (λ)・ρ (λ)) of the light’s spectral distribution P (λ), and the object’s spectral reflectance ρ (λ). This is a strictly physical factor, and its changes can be precisely described with objective numerical data.

As explained in Chapter 13, factor (2) is related to the area of "color perception," where human physiological and psychological elements play a role, influencing the "color" recognized by the brain. This area is extremely complex and varied, with significant individual differences, making it difficult to assess objectively and quantitatively.

However, when the colors of different light sources are similar, it is possible to deal with chromatic adaptation in a somewhat objective and quantitative manner. ≪3≫

(3) Two concepts for evaluation of color rendering properties

If the appearance of colors can vary significantly depending on the light source, what qualifies as a "good" light source? There are two main approaches to assessing the quality of a light source's color rendering:

[A] Fidelity of color reproduction relative to a standard light source

[B] Psychological appeal of color appearance

[A] evaluates a light source based on its ability to replicate the natural appearance of colors humans have experienced throughout history. This method uses a standard light source as a reference and assesses how similarly other light sources can replicate the color appearance of objects under the standard light.

[B], on the other hand, considers a good light source as one that makes colors appear psychologically appealing.

For example, meat that looked red and fresh under a store's lighting may appear less vivid and somewhat darker at home or under natural sunlight, making it seem less fresh. This discrepancy illustrates that a light source rated highly by the standards of [A] may not be evaluated as well under the standards of [B]. Generally, a more vivid appearance is psychologically preferred, as seen in the example of the meat display.

The evaluation method of [B] involves various psychological factors and can vary significantly from person to person, making objective and quantitative assessment challenging.

(4) CIE Color Rendering Index

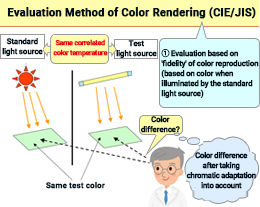

The CIE Color Rendering Index (CRI) is the predominant method used worldwide to evaluate the color rendering of light sources, primarily based on the fidelity of color reproduction relative to a standard light source. This method, defined by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE), assesses how much a set of predefined test color samples changes when illuminated by the test light source compared to a standard light source.

To determine what standard light source to use, the correlated color temperature (CCT) of the test light source is measured in advance, and a standard light source with the same CCT is selected (CIE standard daylight or blackbody radiation). Generally, if the CCT of the test light source is 5,000 K or higher, the standard light source is CIE daylight with the same CCT. If the CCT is below 5,000 K, the standard light source is blackbody radiation of the same CCT. ≪4≫

Aligning the CCT of the standard light source with that of the test light source ensures that the perceived color and psychological impressions are consistent, making accurate evaluations possible. The CRI evaluates the color difference that remains after compensating for the effects of chromatic adaptation.

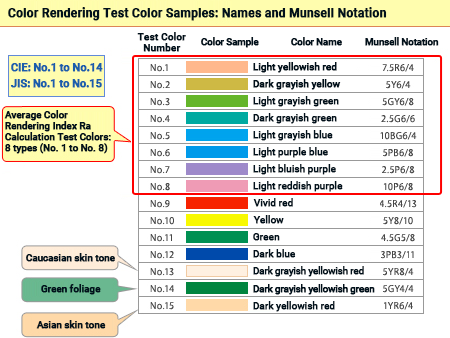

Fourteen standard test colors (fifteen in the Japanese Industrial Standards (JIS), which include an additional color for Asian skin tone) have been predefined by CIE. These test colors include intermediate hues (Munsell saturation 4 to 8), four high-saturation pure colors (red, yellow, green, blue), and colors sensitive to perceived differences, such as Caucasian skin tone and a representative green of foliage. Each test color's spectral reflectance (spectral radiance factor) is precisely defined.

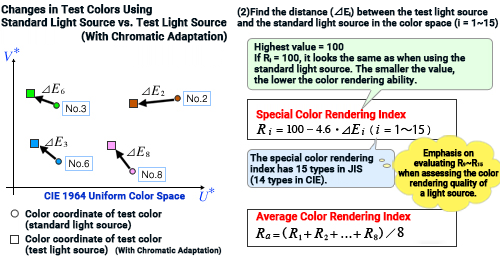

For each test color, the color difference (⊿Ei in the CIE 1964 uniform color space) between illumination by the standard light source and the test light source is calculated after color adaptation. ≪5≫

The special color rendering index Ri for each test color is defined by the formula:

Ri = 100 – 4.6・⊿Ei i = 1 ~ 14 (15)

where ⊿Ei is always non-negative, and Ri values will be less than or equal to 100. An Ri value of 100 indicates perfect color fidelity under both the test and standard light sources. As the color difference increases, the Ri value decreases (poor color rendering).

The average color rendering index Ra is derived from the average of the first eight colors (R1 to R8), providing a standard measure for evaluating the overall color rendering performance of a light source.

(5) Operational Considerations for the CIE Color Rendering Index (CRI)

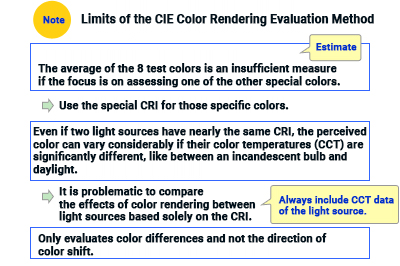

As indicated by the definitions above, the average color rendering index Ra represents the average fidelity of eight representative hues. It provides a general indicator of the overall color rendering quality. However, the color rendering index (Ri) must also be considered to assess the color rendering of specific hues.

It is essential to specify the CCT of the test light source when using Ri and Ra, as these values only have meaning in the context of a specific CCT. Without this, comparing color rendering indices is meaningless, even if the Ra values are similar, as the perceived color can vary significantly with different light source colors.

Furthermore, since the color rendering index is derived from the color difference ⊿Ei between the test and standard light sources, it does not include information about the "direction" of the color shift (e.g., whether the shift is towards red or blue). Thus, while the CRI method quantifies the magnitude of color differences, it does not provide details on the nature of these differences.

(6) Improving the Color Rendering Index (CRI)

Though the CRI is widely used, it has several limitations, including issues in its calculation. ≪6≫ Various new evaluation methods were proposed to improve it, but as of 2015, a new standard has not been established.

Additionally, it is important to note that the current CIE CRI is based on the principle of [A] (faithful color reproduction relative to a reference light source) and not on [B] (psychological preference of color appearance). Research and proposals for an evaluation method based on [B] remain ongoing, and while there is no widely accepted evaluation method, a standard may be developed in the near future.

Comment

≪1≫

Since the dawn of humanity, we have become accustomed to light sources such as sunlight and firelight. Spectrally, these light sources distribute energy continuously across the entire visible range with relatively few peaks and valleys, creating what is known as a continuous spectrum.

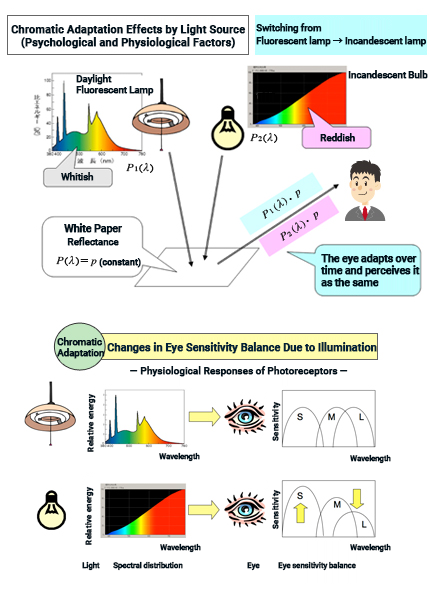

≪2≫ Chromatic adaptation

A common example of color adaptation in daily life is when you are in a room lit by daylight fluorescent lamps and then switch to incandescent lighting. Immediately after switching, the white paper may appear yellow-red, but soon it will look just like it did under fluorescent light. Humans do not only see the "color" of an object; they also recognize what the object is (in this case, "white paper").

Under daylight fluorescent lamps, the L, M, and S cones receive roughly equal stimulation, which the brain interprets as "white." Incandescent light, with its strong long-wavelength (red) component and weak short-wavelength (blue) component, alters the stimulation received from the same paper. Physiological responses adjust the sensitivity of the L cones downward and the S cones upward, countering the physical changes in the incoming light, so the brain still perceives "white." This means the human eye adapts to sudden changes in the spectral distribution of reflected light physiologically by altering the relative sensitivity of its photoreceptors.

In contrast, if you photograph the same paper under both lighting conditions with a camera set to a fixed white balance, the incandescent-lit photo will appear orange due to the difference in spectral distribution. However, if you use auto-white balance, which mimics the human eye’s chromatic adaptation, the photo will appear white regardless of the lighting.

≪3≫ Various color perception effects and the color rendering of light

In our daily visual experiences, it's rare to encounter a scene with just a single color. Multiple colors coexist and change over time, leading to various color perception effects such as simultaneous contrast, successive contrast, and color assimilation, where different colors influence each other. However, when considering the color rendering of a light source, we focus solely on the color adaptation related to the light source itself, excluding the spatial and temporal arrangement of object colors that cause contrast or assimilation effects.

≪4≫ Exceptions for selecting a reference light source

As an exception, cool-white fluorescent lamps with a correlated color temperature of Tcp ≥ 4,600 K use the same correlated color temperature of CIE daylight.

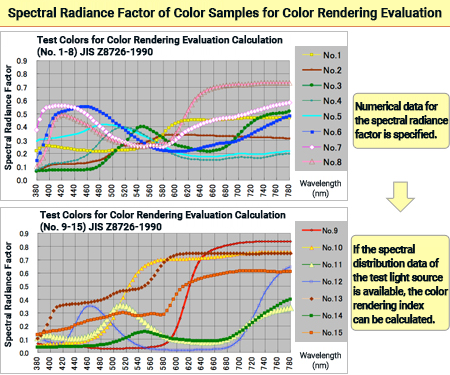

≪5≫ Calculation of color difference ⊿Ei

In evaluating color rendering, the color difference ⊿Ei is calculated using the following:

(1) Spectral distribution data of the reference and test light sources

(2) Spectral reflectance (spectral radiance) of each test color

(3) von Kries coefficient rule

(JIS Z 8726: 1990)

≪6≫ Issues with the current CIE color rendering calculation

The following problems have been pointed out:

(1) It uses the 1964 uniform color space, which was not fully developed as a uniform color space, to calculate the color difference ⊿Ei.

(2) The von Kries coefficient rule for approximate color adaptation correction has been improved since the CIE color rendering evaluation method was established in 1974.